Green Mountains, Red Mountains, and White Mountains (oh my!)

The snowpack in the Sierra Nevada has been delightfully persistent this spring/summer, which is great for backcountry skiing but less great for my desire to go backpacking with my roommate. The rather excellent side effect is that I’ve taken multiple trips up to the Trinity Alps this year, where access to the high country has been relatively easier than in the Sierra. Nestled at the southern end of the Klamath Mountains, the Trinity Alps Wilderness is one of my favorite places in California, and I frankly don’t spend as much time up there as I ought to because of the four hour drive that’s involved with getting to nearly any trailhead. I am grateful for the intervention of the universe that has forced me to point my car north this year.

In my various perusals of hiking blogs, I’ve seen mentions of the “Red Trinities” and the “White Trinities,” a distinction I have always assumed was made due to the different colors of rock. However, every time that I’d hiked in the Trinity Alps they just looked gray to me, so I wasn’t really sure what people were talking about. Some brief googling informed me that the Trinity Alps can roughly be divided into the Green Trinities in the west, named for their abundant timber, the Red Trinities in the east, named for the reddish rocks found in the edge of the mountain range, and the White Trinities in the heart of the wilderness, named for their dramatic, white-gray granitic peaks. Until my most recent trip to the Trinities, I had only been up Canyon Creek and the Stuart Fork trails, which are both in the central White Trinities, explaining why I had never witnessed (dun dun dun)…the other Trinities.

On the weekend before the 4th of July (technically not a long weekend, but pro tip: you can make any weekend a long weekend if you just take Monday off!), my roommate Cassie, our friend Katie and I hiked out of Swift Creek trailhead, at the east end of the wilderness boundary. Our plan was to hike west to Granite Lake, set up camp, and then spend the next day hiking up to Seven Up Pass and then returning to our camp at the lake. The trail follows the path of Swift Creek towards the heart of the Trinity Alps (the source of the creek) with some beautiful meadows and waterfall views along the way. As we climbed upwards and neared Granite Lake, a towering red ridge came into view to the north - our first sighting of the Red Trinities As the trail continued to climb, we could start to see gray mountains straight in front of us and on our left (i.e. west and south) - the White Trinities that are more “classic” Trinity Alps.

Red Trinities tower above us in the north

And the White Trinities coming in hot to the south!

After 5 miles of hiking we reached our destination for the evening:, Granite Lake, a perfect glacial lake appropriately nestled underneath the gray granite ridge. Much to the chagrin of Cassie’s aching feet, we then spent a good hour searching for The Best Possible Campsite. Finding The Best Possible Campsite is a super important thing for me - I love settling into a little nook of nature that feels homey and ideally has a great view of a body of water. After some circling, a creek crossing, and some wandering, we ended up setting up camp (aka throwing down our backpacks and laying out sleeping bags, summer backpacking is the best) at the top of a sweet little bump that gave us a great view of the lake, Granite Peak to the west, and the red ridge and Seven Up Peak to the north. The contrast between the two rock types was strikingly beautiful. We fell asleep under a blanket of endless shooting stars, gently contained by towering multi-colored mountains.

A+ campsite

Where rock types collide!

The next morning we made our way north and west past Granite Lake up towards Seven Up Pass, basically hugging and then winding west up the red ridge. It was a short but sometimes steep hike up to the pass, and well worth it for the gorgeous views of the Four Lakes Loop basin. Once again, we faced the Red Trinities contrasted against the Whites, which continued to be stunning. At this point, I was regretting not having brought our packs up the pass, which would have let us do a loop hike and spend a solid half day hiking through the basin, but that’ll just have to be an adventure for another day.

View from Seven Up Pass. White! Red! White!

I assume that by now you are wondering, “but why Katy? Why are there different kinds of rocks in the Trinity Alps?” The different colored rocks of the Trinity Alps has to do with the geologic history of the mountain range, and in fact of the entire Klamath Mountains, which happens to be fairly complex and fascinating. I found a book chapter about the natural history of the Klamaths, which had this to say:

“The region’s complex pattern of mountains and rivers creates a bewildering set of landscapes… Rocks laid in the distant past tell stories of ancient seas, of landmasses from throughout the world that have been added to North America, and of lofty mountain ranges that have worn down only to rise again. Pleistocene ice and now today’s events mold the area’s rivers and mountains. No wonder the area is confusing.” - Northwest California, A Natural History (John Sawyer)

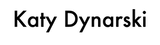

So! The bar for complexity is set high, but I will do my best to explain. This particular geologic story begins in the Mesozoic era, about 400 million years ago, when the California land mass was much smaller than it is today - the Klamath Mountains and Coast Ranges weren’t attached to the land at all. The rocks that make up the Klamath Mountains were once volcanic islands and other bits of the ancient ocean floor. The ocean floor isn’t static - it moves outward from spreading centers, and can collide with continents at what are known as convergent boundaries. About 400 million years ago, the ocean floor in the Pacific Ocean collided with the west coast of ancient North America, and because the rocks that make up the ocean floor are much heavier than the rocks that make up the continent, the ocean floor slid under continental North America, a process called subduction. As the ocean floor slid under the land, some of the seafloor (especially the volcanic islands) got scraped off the ocean plate and stuck onto the continent, which we call accretion. This happened 8 times over the course of the next ~300 million years. Ocean floor and volcanic rocks are heavy, and rich in iron and magnesium (a characteristic we describe as mafic). This is the basis for the red rocks found throughout the Klamath Mountains (including the Trinity Alps) and the coast ranges.

So Red Trinities? Check. What about the White Trinities? Where did that granite come from? As the ocean floor moved under the North American plate, its rocks heated and some melted, producing magma. This magma bubbled up into the continental crust, but some of it cooled before ever breaking the surface, basically a volcano that lost its steam. When magma cools slowly underground like this, it results in coarse grained rock called a pluton - pluton just describes any mass of rock that cooled and formed underground, a la the cooled magma chamber of a volcano. The White Trinities are made up of granodiorite plutons that formed from this process.

The diagram below does a pretty decent job at showing both the accretion process and the subsequent ocean floor melting/bubbling up/cooling that produces plutons. I stole it from a nifty little American Geophysical Union blog post that describes subduction and accretion far better than I can.

The geology of the Klamaths becomes even more complicated due past glaciation as well as lots of metamorphic action caused by all of the pressure and stress of those eight accretions - all that pushing and scraping produced so much heat and pressure that rocks got squished and melted, changing both their texture and chemistry. That’s an explanation that I’ll shelf for now - but check out the reference at the end of this post if you’re interested in the metamorphic history of the mountain range. It is truly fascinating.

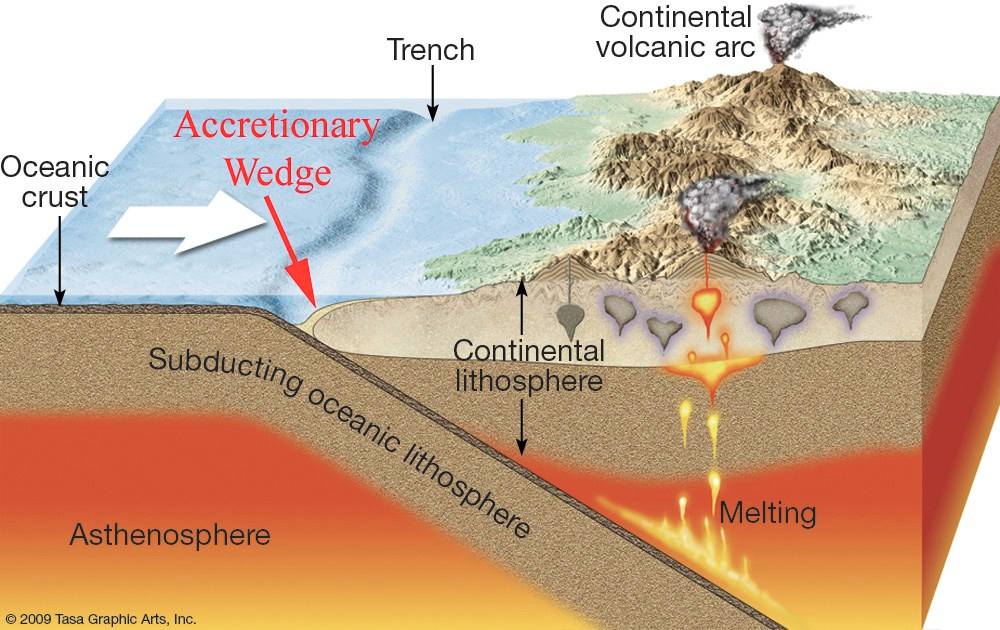

Because I have a serious armchair geology problem as well as a deep and undying obsession with CalTopo, when I got home from our backpacking trip I did the most reasonable thing to do, which was overlay our hiking route on a geologic map of the area and see if our views matched up with how the rocks were mapped. I assume this is a thing that everyone does either before or after hikes, and I’m not interested in hearing otherwise. On this map, our route is shown in red, and a few points (aka the start, camp spot, and the pass we hikes to) are marked with red X’s. The colors overlaid on the satellite image show what the different rocks are mapped as. The granodiorite (“white”) Trinities are shown in orange (I didn’t pick the colors) and the ultra-mafic (“red”) Trinities are shown in red. There’s also some yellow, which shows glacial till (rocks that got moved around by glaciers when the region was glaciated). The views on our hike match the map pretty darn well! On day one, we hiked west from the start point the the Best Campsite Ever. You can see the red, ultra-mafic ridge to our north as we hiked to the lake, and then the granitic area to the west that we could see from our campsite.

Geologic map for our hike in to Granite Lake!

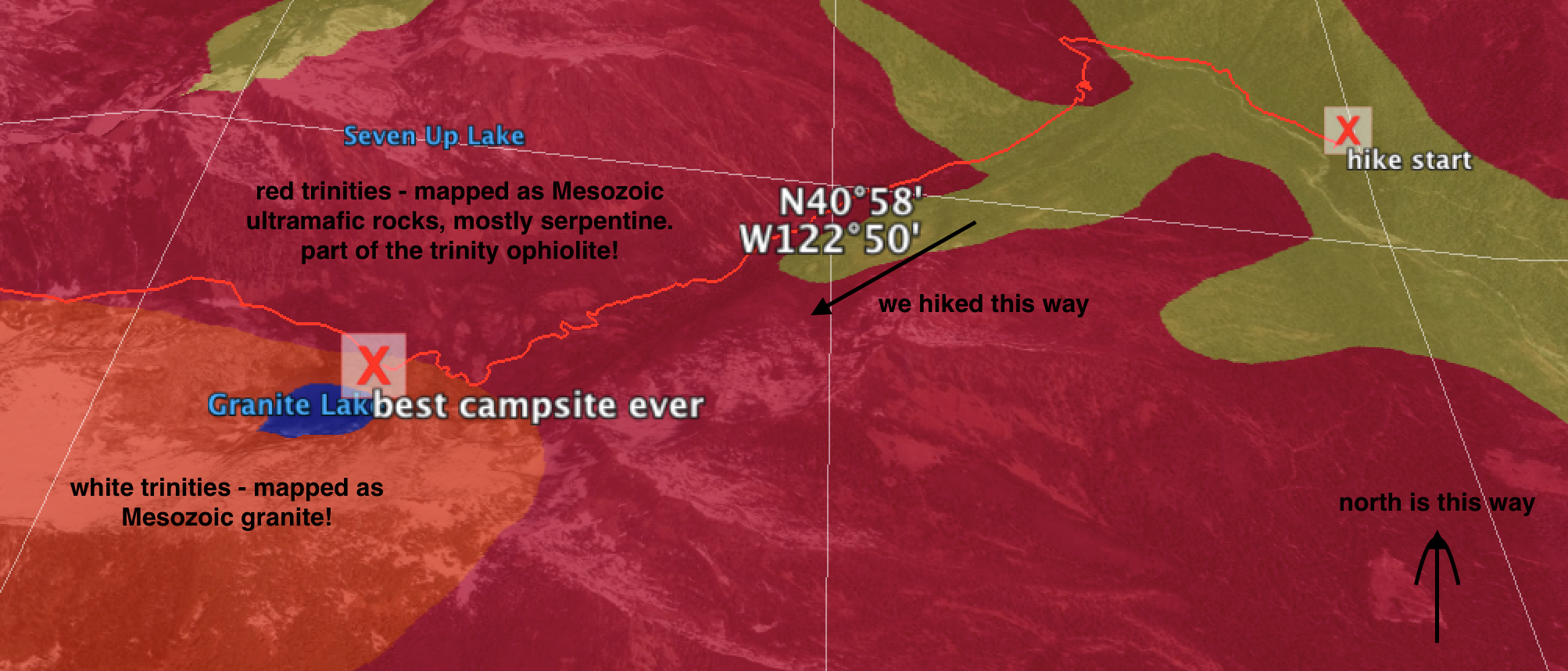

On day two, we continued west past the lake to Seven Up Pass. If you imagine yourself standing on the pass looking westward over the basin, you can see the granite unit next to the ultra-mafic unit once again, giving that awesome contrast between the white and red Trinities.

Map of our view from Seven Up Pass (note that north is oriented to the right)

And oh how well the map matches our view! (Also how cute are we?!)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I really love doing this kind of thing. I think it’s super fun to learn a little bit about the history of an area, be it on a geologic time scale or a human time scale, especially when that information explains something that is cool, beautiful, or otherwise unique about that area. Knowing about the rocks that give rise to the epic beauty of the Trinities makes me feel more connected to these mountains that I already loved, which in turn makes me enjoy hiking there even more. This is part of why I love being a biogeochemist; working to understand a little bit more about the world around me gives even more meaning to the places that already fill me with awe. It’s fun to remember that although I don’t have to be constantly engaged in my research no matter where I go (in fact, it would be super unhealthy to do that), it’s always possible to learn a little but more about the places I love by taking a look at a map, pulling out a plant guide, or heck, looking at Wikipedia.

Also, I sometimes feel that as an earth scientist I’m supposed to have a decent understanding of plate tectonics and take it for granted that duh the continents travel around on these plates that sometimes smash into each other and sometimes one runs the other one over and one melt. However, every time I think about plate tectonics and the formation of mountains as we know them today, my mind is absolutely blown. Childish as it may be, I try my best to hold onto this sense of wonder and not become desensitized to just how cool our planet is. In a recent episode of This American Life, Ira Glass talks about magic tricks, and how sometimes understanding the underlying mechanics of a magic trick is way cooler than just watching the trick itself. I feel this way about the mountains; there is a certain magic that I feel within the mountains, and gaining an understanding of the processes that shaped and continue to shape these places deepens my sense of awe.

You can read about the geologic history of the Klamath Mountains here. And, you can download a KML file with a geologic map of your state (viewable in Google Earth) here. Happy hiking!

Major disclaimer: I am not a geologist. I may have made mistakes in this explanation/map interpretation/etc. If you find a mistake, please let me know so I can correct it!